Article

Unveiling the evidence gap: Orphan drugs vs. non-orphan drugs in German health technology assessments

Drugs for rare diseases are often prejudged to lack evidence because they have a guaranteed additional benefit by law. But is this prejudice justified? This article takes you on an enlightening exploration of health technology assessment in Germany to elucidate the reality behind these lingering assumptions.

Rare diseases and their treatments in German HTA

Rare diseases, which by definition affect only 1 in 2,000 people in the European Union, often lack effective treatment options. Orphan drugs (ODs) fill this gap and therefore receive special incentives for their development and commercialisation. For market access in Germany, ODs receive a unique treatment in health technology assessment (HTA).

The German HTA for medicinal products is regulated by the ‘Arzneimittelmarktneuordnungsgesetz’ (Pharmaceuticals Market Reorganisation Act, AMNOG). AMNOG aims to balance reimbursement for pharmaceutical manufacturers and the expenditure burden for the national healthcare system. Medicinal products are obligated to undergo a benefit assessment in comparison to an existing standard therapy (the so-called appropriate comparative therapy [ACT]). A benefit assessment is mandatory when launching a newly authorised medicinal product with a new active substance in Germany or for newly authorised indications of an already assessed drug. Based on the clinical evidence, the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) assesses the added medical benefit using six categories (‘major’, ‘considerable’, ‘minor’, ‘non-quantifiable’, ‘no added benefit’, or ‘less’).

For ODs, an added medical benefit is granted by law, and the extent assessment is based on pivotal evidence without the obligation to compare against an ACT. However, if sales reach €30 million or the indication loses orphan status, reassessment under the standard evaluation process becomes mandatory. Non-orphan drugs (non-ODs), being obligated to the regular benefit assessment, may also be subjected to a reassessment, either mandatorily in case of temporary decisions (e.g. additional data are requested by the G-BA) or at the request of the pharmaceutical manufacturer.

The benefit assessment is the basis for the price negotiation for reimbursement between the pharmaceutical manufacturer and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds (GKV-SV). Only drugs with an added medical benefit can achieve a higher price than the costs for the ACT in the price negotiation. Within the first six months after launch, the manufacturer is free to define the launch price, while the negotiated price is applied from the seventh month. The reimbursement price for a drug may further change with time when reassessments and new indications for the respective drug pass through HTA and subsequent price negotiations.

This article explores the results of an in-depth analysis of German HTAs centering on the comparison of evidence criteria and pricing between ODs and non-ODs (for both initial assessment and reassessment) and aims to shed light on whether ODs lack evidence in HTA compared to non-ODs.

A comprehensive review analysed benefit assessments for ODs and non-ODs from 2011 to May 2024 from a database of G-BA data. This analysis included 959 benefit assessments. Of these, 810 were initial assessments of newly authorised drugs or newly authorised indications of a drug, while 149 were reassessments, with some products being reassessed more than once for a respective indication. The analysis of 810 initial benefit assessments revealed that 27% of the assessments evaluated ODs, while 73% were non-ODs. In total, a reassessment was performed for 15% of all assessments (7% ODs and 8% non-ODs).

Any reassessments were matched to the respective initial benefit assessment, if applicable, to align related assessments for the same drug. Data were extracted for ODs and non-ODs focusing on parameters such as evidence assessed (study types, number of studies, and size of studies), level of added benefit granted, and price. Evaluations focused on cases with both initial assessment (60 ODs and 64 non-ODs) and reassessment (54 ODs and 70 non-ODs, reflecting that some drugs lost OD status from a prevalence perspective and were reassessed under the standard procedure as non-ODs) for a given indication to assess whether evidence, level of benefit, and price changed between initial assessment and reassessment, and to compare between ODs and non-ODs.

For ODs, an added medical benefit is granted by law, and the extent assessment is based on pivotal evidence without the obligation to compare against an ACT. However, if sales reach €30 million or the indication loses orphan status, reassessment under the standard evaluation process becomes mandatory. Non-orphan drugs (non-ODs), being obligated to the regular benefit assessment, may also be subjected to a reassessment, either mandatorily in case of temporary decisions (e.g. additional data are requested by the G-BA) or at the request of the pharmaceutical manufacturer.

The benefit assessment is the basis for the price negotiation for reimbursement between the pharmaceutical manufacturer and the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds (GKV-SV). Only drugs with an added medical benefit can achieve a higher price than the costs for the ACT in the price negotiation. Within the first six months after launch, the manufacturer is free to define the launch price, while the negotiated price is applied from the seventh month. The reimbursement price for a drug may further change with time when reassessments and new indications for the respective drug pass through HTA and subsequent price negotiations.

This article explores the results of an in-depth analysis of German HTAs centering on the comparison of evidence criteria and pricing between ODs and non-ODs (for both initial assessment and reassessment) and aims to shed light on whether ODs lack evidence in HTA compared to non-ODs.

A comprehensive review analysed benefit assessments for ODs and non-ODs from 2011 to May 2024 from a database of G-BA data. This analysis included 959 benefit assessments. Of these, 810 were initial assessments of newly authorised drugs or newly authorised indications of a drug, while 149 were reassessments, with some products being reassessed more than once for a respective indication. The analysis of 810 initial benefit assessments revealed that 27% of the assessments evaluated ODs, while 73% were non-ODs. In total, a reassessment was performed for 15% of all assessments (7% ODs and 8% non-ODs).

Any reassessments were matched to the respective initial benefit assessment, if applicable, to align related assessments for the same drug. Data were extracted for ODs and non-ODs focusing on parameters such as evidence assessed (study types, number of studies, and size of studies), level of added benefit granted, and price. Evaluations focused on cases with both initial assessment (60 ODs and 64 non-ODs) and reassessment (54 ODs and 70 non-ODs, reflecting that some drugs lost OD status from a prevalence perspective and were reassessed under the standard procedure as non-ODs) for a given indication to assess whether evidence, level of benefit, and price changed between initial assessment and reassessment, and to compare between ODs and non-ODs.

Comparability of presented evidence for ODs and non-ODs

For ODs, an added benefit is automatically granted by law. Hence, what clinical evidence is presented for ODs in benefit assessments, and how does it differ from non-OD assessments? As a first step in standard benefit assessments, the G-BA assesses the quality of the submitted studies based on the level of evidence to provide a sufficiently reliable level of knowledge. Based on this evaluation, the study is either accepted or not considered in the assessment. Further, studies provided for a standard benefit assessment must include a comparison of the medicinal product with the ACT, defined by the G-BA. While ODs benefit from a less stringent execution of evidence criteria for initial assessments, those that exceed the sales limit are reassessed under the standard procedure even if they retain orphan status from a prevalence perspective.

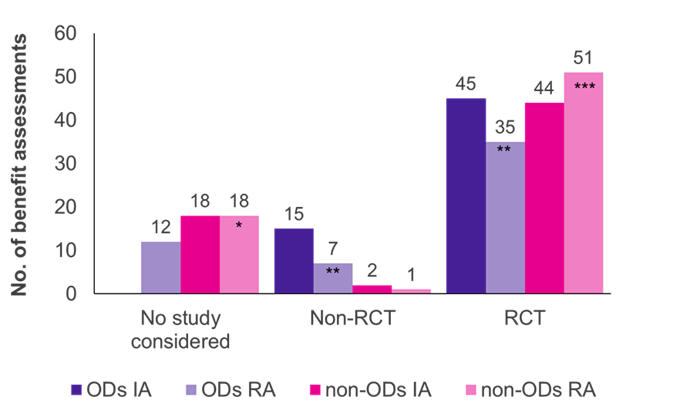

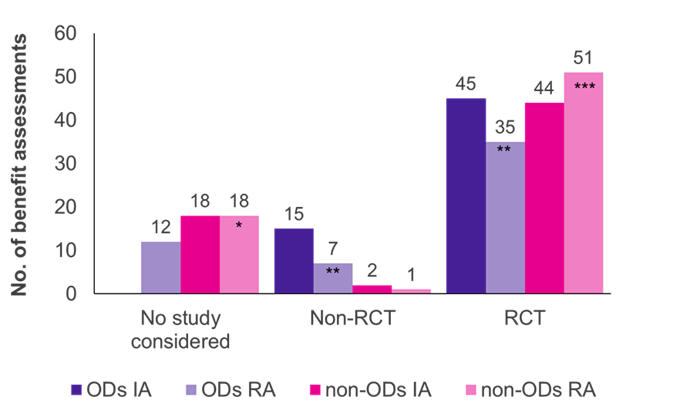

The evaluations showed that randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the gold standard of evidence, were the predominant study type for both ODs and non-ODs (Figure 1). For non-ODs, more RCTs were accepted by the G-BA in reassessment (51/70 cases, 73%) than in initial assessment (44/64 cases, 69%), while it was vice versa for ODs (45/60 initial assessments, 75%; 35/54 reassessments, 65%).

Initially, the clinical studies submitted by the manufacturer were accepted by the G-BA in all OD assessments; the majority of studies (45/60 cases, 75%) were RCTs, and 25% (15/60 cases, 25%) were non-RCTs (e.g. single-arm trials, small study sizes, use of surrogate outcomes). When ODs were reassessed in a standard benefit assessment, having exceeded the sales limit, the proportion of accepted RCTs and non-RCTs decreased to 65% (35/54 reassessments) and 13% (7/54 reassessments), respectively. In 12 of the OD reassessments (22%), the respective studies were not accepted by the G-BA, reflecting the more stringent evidence criteria applied under the standard assessment process. Not meeting the ACT might be the main reason for this shift.

In contrast to ODs, very few non-RCTs were accepted in non-OD benefit assessments (2/64 initial assessments; 1/70 reassessments). Thus, non-RCTs appear more likely to be accepted for ODs than for non-ODs. Further, the manufacturer’s evidence was accepted in all OD initial assessments, whereas the presented studies were rejected in 18 assessments and reassessments of non-ODs. This is due to the fact that in OD assessments pivotal studies are always accepted by law.

Figure 1. Distribution of study type among ODs and non-ODs in the initial assessment (IA) and reassessment (RA)

Key: IA – initial assessment; No. – number; OD – orphan drug; RA – reassessment; RCT – randomised controlled trial.

Furthermore, and not surprisingly, there was a positive correlation between an increased size of study populations and the availability of an RCT (data not shown).

Initially, the clinical studies submitted by the manufacturer were accepted by the G-BA in all OD assessments; the majority of studies (45/60 cases, 75%) were RCTs, and 25% (15/60 cases, 25%) were non-RCTs (e.g. single-arm trials, small study sizes, use of surrogate outcomes). When ODs were reassessed in a standard benefit assessment, having exceeded the sales limit, the proportion of accepted RCTs and non-RCTs decreased to 65% (35/54 reassessments) and 13% (7/54 reassessments), respectively. In 12 of the OD reassessments (22%), the respective studies were not accepted by the G-BA, reflecting the more stringent evidence criteria applied under the standard assessment process. Not meeting the ACT might be the main reason for this shift.

In contrast to ODs, very few non-RCTs were accepted in non-OD benefit assessments (2/64 initial assessments; 1/70 reassessments). Thus, non-RCTs appear more likely to be accepted for ODs than for non-ODs. Further, the manufacturer’s evidence was accepted in all OD initial assessments, whereas the presented studies were rejected in 18 assessments and reassessments of non-ODs. This is due to the fact that in OD assessments pivotal studies are always accepted by law.

Figure 1. Distribution of study type among ODs and non-ODs in the initial assessment (IA) and reassessment (RA)

Key: IA – initial assessment; No. – number; OD – orphan drug; RA – reassessment; RCT – randomised controlled trial.

Note: Six ODs, initially assessed as ODs, were reassessed as non-ODs due to loss of OD status (*added four former ODs; **reduced by three former ODs; ***added two former ODs).

Furthermore, and not surprisingly, there was a positive correlation between an increased size of study populations and the availability of an RCT (data not shown).

Distribution of granted added benefits for ODs and non-ODs in initial assessment

The degree of the granted added benefit is linked to the provided evidence. Noteworthy, granting ‘no added benefit’ is not applicable for ODs in the benefit assessment, and the default degree of added medical benefit is ‘non-quantifiable’. Most OD initial assessments result in a ‘non-quantifiable’ benefit (Figure 2). For non-ODs, the most assigned benefit category was ‘no added benefit’. The distribution of a granted added benefit in the categories ‘considerable’ and ‘minor’ was more or less comparable in OD and non-OD initial assessments.

Figure 2. Granted added benefit in initial assessments

Figure 2. Granted added benefit in initial assessments

Key: No. – number; OD – orphan drug.

Benefit assessments result in a decrease of reimbursement prices (similar to ODs and non-ODs)

An analysis of the price levels before benefit assessment and after price negotiation showed a reduction of the launch price through the procedure of an initial assessment (OD: 18% rebate; non-OD: 22% rebate). A reassessment led to a further increase in the rebate, although to a lesser extent (8% rebate after reassessment for both ODs and non-ODs). The price difference between ODs and non-ODs is large. On average, ODs were found to be approximately 10.2 to 13.5 times more expensive than non-ODs. This cost difference persisted at launch, after initial benefit assessment, and across reassessments (data not shown).

Orphan drugs: Balancing high costs with strong evidence

The analysis showed how ODs, with typically higher prices and less robust evidence than non-ODs, are assessed in the German healthcare system. While ODs constitute a small fraction of benefit assessments, their considerable expenses, reflected by the high reimbursement prices compared to non-ODs, underscore their significant impact on the healthcare system. The elevated cost of ODs is influenced by multiple factors, notably the restricted patient population and the substantial research and development investments. Particularly, the high costs of ODs are repeatedly discussed in terms of whether their price is justified in relation to the provided evidence, especially when considering the economic burden on healthcare systems.

The analyses indicated comparability in the presented evidence, with RCTs providing the evidence base for the majority of assessments for both ODs and non-ODs. As shown by the data, the OD status is not necessarily associated with a lack of quality of evidence, which has been the subject of debates. However, the reduction in accepted studies for ODs in the reassessment emphasises the difficulties of addressing the ACT. As anticipated, the small prevalence associated with rare diseases leads to challenges in conducting extensive RCTs, highlighting the correlation between disease prevalence and quality of evidence. However, it was shown that pharmaceutical companies submit high-quality evidence, with a significant number of RCTs conducted for ODs, despite the constraints mentioned above.

In conclusion, drugs developed for rare diseases present distinct challenges for manufacturers and HTA authorities. While ‘assessment privileges’ improve the availability of therapies for difficult-to-treat rare conditions, caution is warranted when evidence-based medicine criteria are applied. Our findings demonstrate that despite the obstacles faced by ODs, high-quality evidence in the form of RCTs is provided. However, the HTA system recognises the occasional infeasibility of RCTs in the field of rare diseases, while allowing more leeway in accepting non-RCTs in OD assessments.

While this article did not delve into the justification of ODs’ high prices, their efficacy correlation, or the rationale behind the granted added benefit, further evaluation is warranted to analyse these key aspects and their complexity within the German healthcare system. The interplay between the costs of ODs, the strength of evidence they offer, and the value they bring to healthcare systems remains a complex and evolving topic that necessitates continued scrutiny and analysis.

In conclusion, drugs developed for rare diseases present distinct challenges for manufacturers and HTA authorities. While ‘assessment privileges’ improve the availability of therapies for difficult-to-treat rare conditions, caution is warranted when evidence-based medicine criteria are applied. Our findings demonstrate that despite the obstacles faced by ODs, high-quality evidence in the form of RCTs is provided. However, the HTA system recognises the occasional infeasibility of RCTs in the field of rare diseases, while allowing more leeway in accepting non-RCTs in OD assessments.

While this article did not delve into the justification of ODs’ high prices, their efficacy correlation, or the rationale behind the granted added benefit, further evaluation is warranted to analyse these key aspects and their complexity within the German healthcare system. The interplay between the costs of ODs, the strength of evidence they offer, and the value they bring to healthcare systems remains a complex and evolving topic that necessitates continued scrutiny and analysis.

Sources

-

Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (BMG). Seltene Erkrankungen. 2024. Accessed 4 September 2024. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/themen/praevention/gesundheitsgefahren/seltene-erkrankungen.html

-

Bundesministerium der Justiz (BMJ). Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) Fünftes Buch (V). Accessed 4 September 2024. https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/sgb_5/__35a.html

-

Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen. Preis- und Kostenentwicklung von Orphan Drugs; Arbeitspapier [online]. 2024. Accessed 19 September 2024. https://dx.doi.org/10.60584/GA22-01