Article

HTA in Japan: The glass remains half full (for now)

Is the glass half empty or half full? When it comes to health technology assessment (HTA) in Japan, the answer to that question depends very much on who you are. If you are the Japanese Ministry of Finance, you would criticise the current system for not doing enough to control the cost of medicines. And if you are a pharmaceutical industry association, you would likewise criticise the system but from an opposing perspective, highlighting flaws in the present HTA system such as a lack of clarity and imperfect scientific decision-making. But to more neutral observers the glass looks not half empty but half full; is an HTA system that assesses only a small minority of products not a barrier to access, resulting in only small price adjustments? It could be, and in many countries is a lot worse.

How does it work?

The Japanese government first began using HTA for cost-effectiveness evaluation in 2016 on a “pilot” basis and made the system permanent in 2019. The Chuikyo, the Central Social Insurance Medical Council, selects the drugs for HTA assessment, usually at their time of National Health Insurance (NHI) listing, from those which are deemed either to have “large” sales, defined as greater than Y5 billion (c.$35 million) forecasted revenue at peak year, or to have a “significantly high” unit cost (undefined). In addition, drugs for “intractable diseases” (rare conditions for which treatment options are limited) and for pediatric use are exempt. These criteria, and a shortage of health economists in Japan, mean that the vast majority of pharmaceutical products that come here are never subject to HTA; by mid-2024 only 50 products in total had been so assessed.

If a product is selected, the approximately one-year process is overseen by the quasi-governmental organisation C2H, with analysis by the company taking 6 to 9 months and the public analysis then taking 3 to 6 months. An incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) is calculated for the product, and when the ICER exceeds Y5 million (Y7.5 million in some cases, so c.$34,000 or c.$51,000) per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), the premium part of the price will be adjusted.

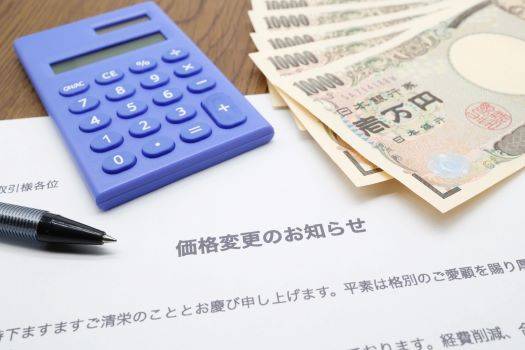

So, one key difference between the HTA system in Japan and many other countries is that the assessment is after the product has launched and been reimbursed, somewhat similar in timing to the “clawback” process in Germany. Another key difference is that the results of the evaluation will be used for reimbursement price adjustment, not for a coverage decision, and then not an adjustment of the full price but only of any premiums agreed at the NHI price listing. This makes Japan’s HTA system fundamentally different from those in some other countries: it is a post-launch price adjustment mechanism, not a reimbursement hurdle at launch.

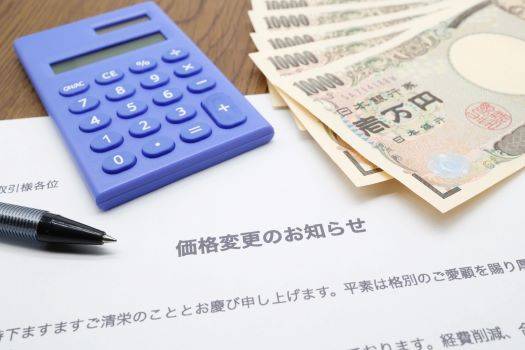

How big are typical price adjustments in Japan? To give some examples: Novo Nordisk’s oral GLP-1 treatment for diabetes, Rybelsus®, received a 2.6% price cut in November 2022; for June 2023, Takeda’s Revestive® for short bowel syndrome received a 7.0% cut, and Lilly’s migraine treatment Emgality® a 5.0% cut; MSD’s oral COVID-19 pill Lagevrio® received an 8.2% price cut in July 2024; and Lilly’s diabetes treatment Mounjaro® received no price cut but had the request for a price increase rejected in September 2024. So, reasonable expectations for a company whose product is selected for HTA are: (i) it will likely get a price cut a year or two after launch, even if you think it should not and if anything there should be an increase—this system was not introduced to push up the drugs bill, after all; and (ii) the cut will be in single-digit percentage terms. Are such outcomes a cause for celebration in corporate boardrooms? No. But they are not catastrophic to most business cases and compare favorably to some of the HTA outcomes in other markets where reimbursement may be completely denied.

So, one key difference between the HTA system in Japan and many other countries is that the assessment is after the product has launched and been reimbursed, somewhat similar in timing to the “clawback” process in Germany. Another key difference is that the results of the evaluation will be used for reimbursement price adjustment, not for a coverage decision, and then not an adjustment of the full price but only of any premiums agreed at the NHI price listing. This makes Japan’s HTA system fundamentally different from those in some other countries: it is a post-launch price adjustment mechanism, not a reimbursement hurdle at launch.

How big are typical price adjustments in Japan? To give some examples: Novo Nordisk’s oral GLP-1 treatment for diabetes, Rybelsus®, received a 2.6% price cut in November 2022; for June 2023, Takeda’s Revestive® for short bowel syndrome received a 7.0% cut, and Lilly’s migraine treatment Emgality® a 5.0% cut; MSD’s oral COVID-19 pill Lagevrio® received an 8.2% price cut in July 2024; and Lilly’s diabetes treatment Mounjaro® received no price cut but had the request for a price increase rejected in September 2024. So, reasonable expectations for a company whose product is selected for HTA are: (i) it will likely get a price cut a year or two after launch, even if you think it should not and if anything there should be an increase—this system was not introduced to push up the drugs bill, after all; and (ii) the cut will be in single-digit percentage terms. Are such outcomes a cause for celebration in corporate boardrooms? No. But they are not catastrophic to most business cases and compare favorably to some of the HTA outcomes in other markets where reimbursement may be completely denied.

Where are we headed?

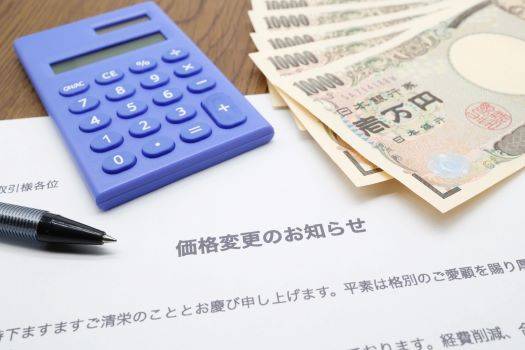

If Japan’s HTA system is more of a minor negative for the pharmaceutical industry than a major disincentive, might the system evolve in a way that would cause the manufacturers more distress? Well, there are certainly those who want to see such an evolution, principally in the Ministry of Finance (MoF). This most powerful of Japan’s ministries has publicly stated its support for the system being used for a larger number of products and for yes/no reimbursement decisions at launch. But, at the moment, the winds in Japan are blowing in a pro-innovation direction, as evidenced by the package of positive changes to the pricing system implemented in April 2024. It looks unlikely that the MoF will get its way anytime soon.

That does not mean that the HTA system in Japan could not worsen from an industry perspective. Industry associations have already voiced concerns about the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s decision to consider expansion of cost-effectiveness evaluations in the FY2026 system reforms, which might include increasing the number of innovative medicines subject to price cuts and the magnitude of those cuts. But it would be counter-productive for Japan, at a time when it is trying to shrink its “drug lag” and “drug loss” problems, to turn its HTA system into a more significant disincentive to innovation. There is still time for that to be understood.

This article summarises Cencora’s understanding of the topic based on publicly available information at the time of writing (see listed sources) and the authors’ expertise in this area. Any recommendations provided in the article may not be applicable to all situations and do not constitute legal advice; readers should not rely on the article in making decisions related to the topics discussed.

Connect with our team

Our team of leading value experts is dedicated to transforming evidence, policy insights, and market intelligence into effective global market access strategies. Let us help you navigate today’s complex healthcare landscape with confidence. Reach out to discover how we can support your goals.

Sources

- MOF Ramps Up Push for Use of Cost-Effectiveness Assessment in Reimbursement Decisions, Pharma Japan, 17 April 2024.

- Building sustainable Pharmaceutical Innovation Ecosystems through effective Health Technology Assessment (HTA) review in Japan, EFPIA Japan, 7 June 2024.

- Current status of health technology assessment research in Japan, Annals of Clinical Epidemiology, May 2023.

- Japan’s NHI Drug Price System, Yukio Abe, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), 2022.

- Building sustainable Pharmaceutical Innovation Ecosystems through effective Health Technology Assessment (HTA) review in Japan, EFPIA Japan, 7 June 2024.

- C2H website: https://c2h.niph.go.jp/en/

- Cost effectiveness evaluation of health care technologies in Japan: New HTA system and the role of C2H, Fukuda and Shiroiwa, Center for Outcomes Research and Economic Evaluation for Health, National Institute of Public Health, 2021.

- Rybelsus Faces 2.5-2.6% Price Cut in November under CEA Scheme; No Change for Cabometyx, Pharma Japan, 10 August 2022.

- Emgality, Veklury, and More to Get Lower Prices in June: CEA Scheme, Pharma Japan, 9 March 2023.

- Lagevrio to Get 8.2% Price Cut in July, 2.7% for Kerendia: CEA, Pharma Japan, 11 April 2024.

- Mounjaro to Keep Price after CEA as Lilly’s Appeal for Raise Nixed, Pharma Japan, 12 September 2024.

- MOF Ramps Up Push for Use of Cost-Effectiveness Assessment in Reimbursement Decisions, Pharma Japan, 17 April 2024.

- Joint Statement on FY2025 Off-Year Drug Price Revision Outcome, Cost-Effectiveness Evaluations and Mandatory Drug Discovery Support Fund, PhRMA Japan and EFPIA Japan, 24 December 2024.