Early network mapping to guide HTA literature reviews—how do we identify the right evidence efficiently?

The best approach to limit the amount of literature to screen for an HTA-compliant review is to include search terms for the comparators of interest. Ultimately, the comparators of interest will be determined by the HTA body conducting the assessment and defined in the assessment scope. While the final scope may allow for more focused comparators, SLRs must start well before the determination of the final scope, leaving manufacturers to anticipate the comparators.

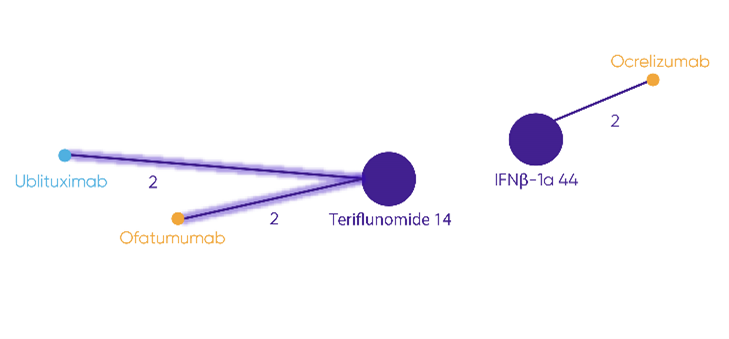

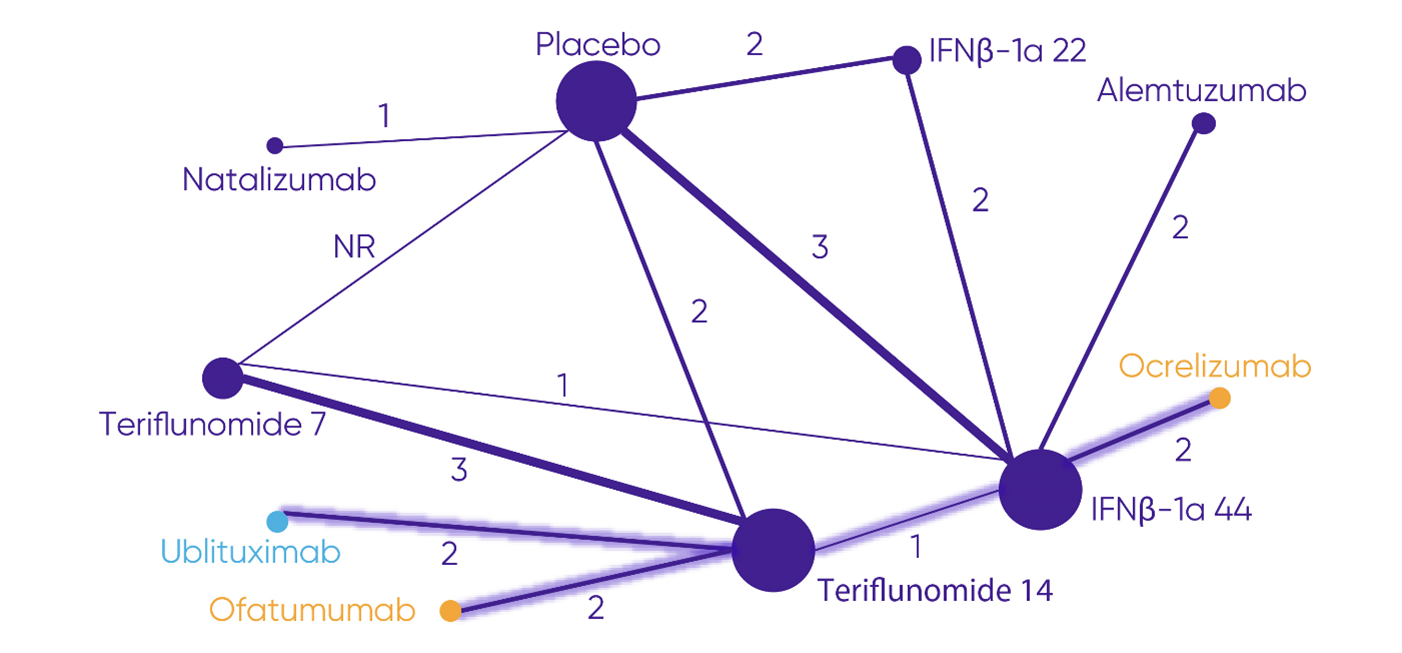

While there are multiple activities to aid in anticipating the scope, once that has been completed, it is tempting to conduct an SLR including only the comparators of interest. However, there is a danger that comparator limits may result in a disconnected network if a network meta-analysis (NMA) is to be conducted as part of the submission.

Note: Highlighted lines show trials connecting ublituximab and ofatumumab. No connection is possible to ocrelizumab.

Adapted from NICE. Committee Papers. Ublituximab for treating relapsing multiple sclerosis [ID6350]. 18 December 2024b.

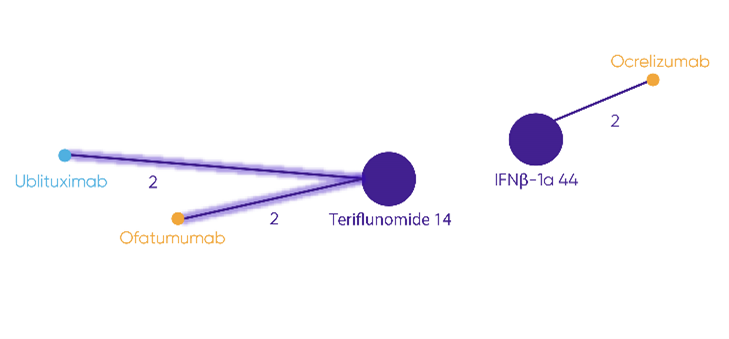

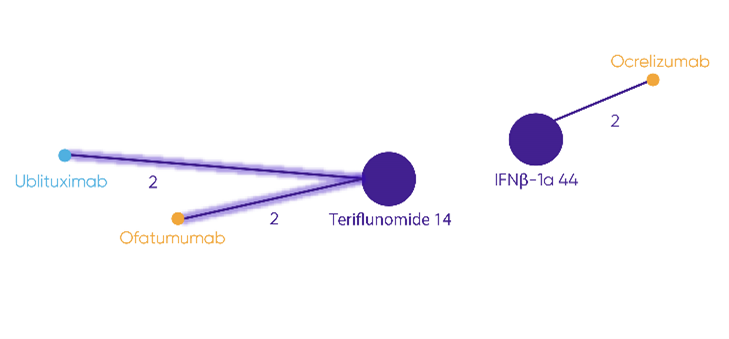

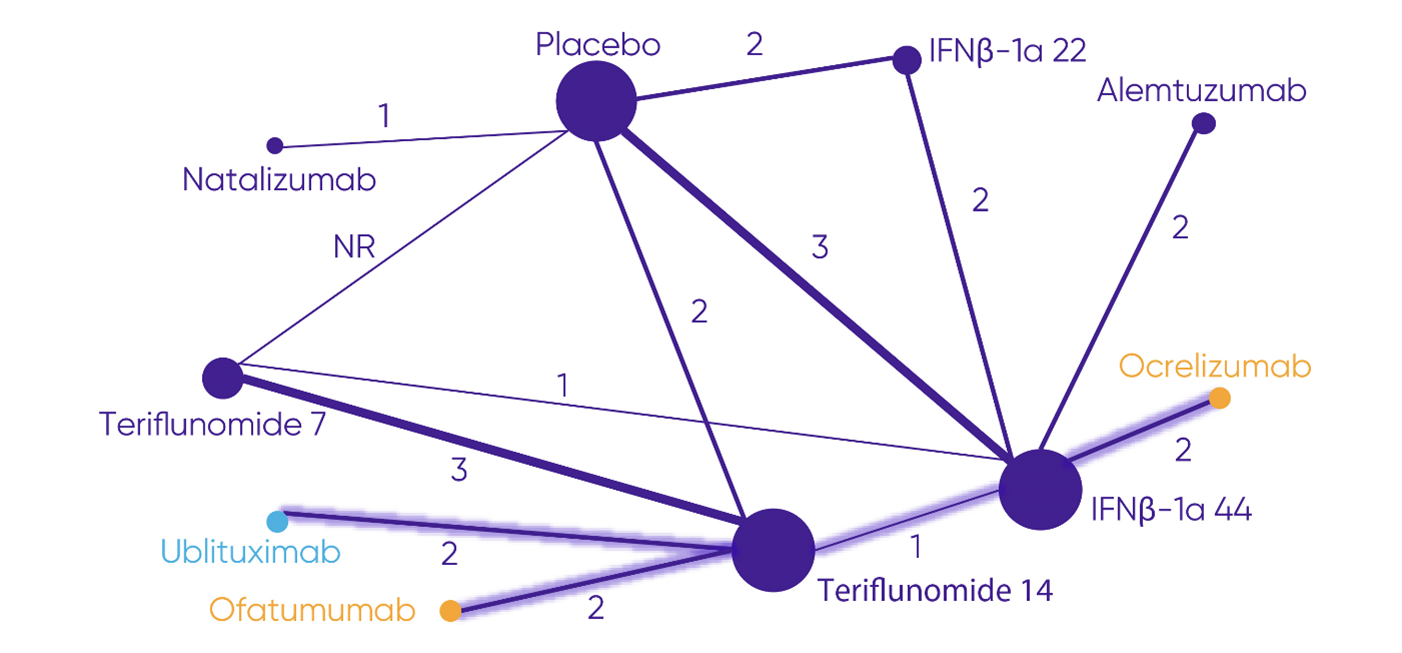

Note: Highlighted lines show the most direct connection from ocrelizumab to ublituximab and ofatumumab.

Adapted from Ublituximab for Treating Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis [ID6350].

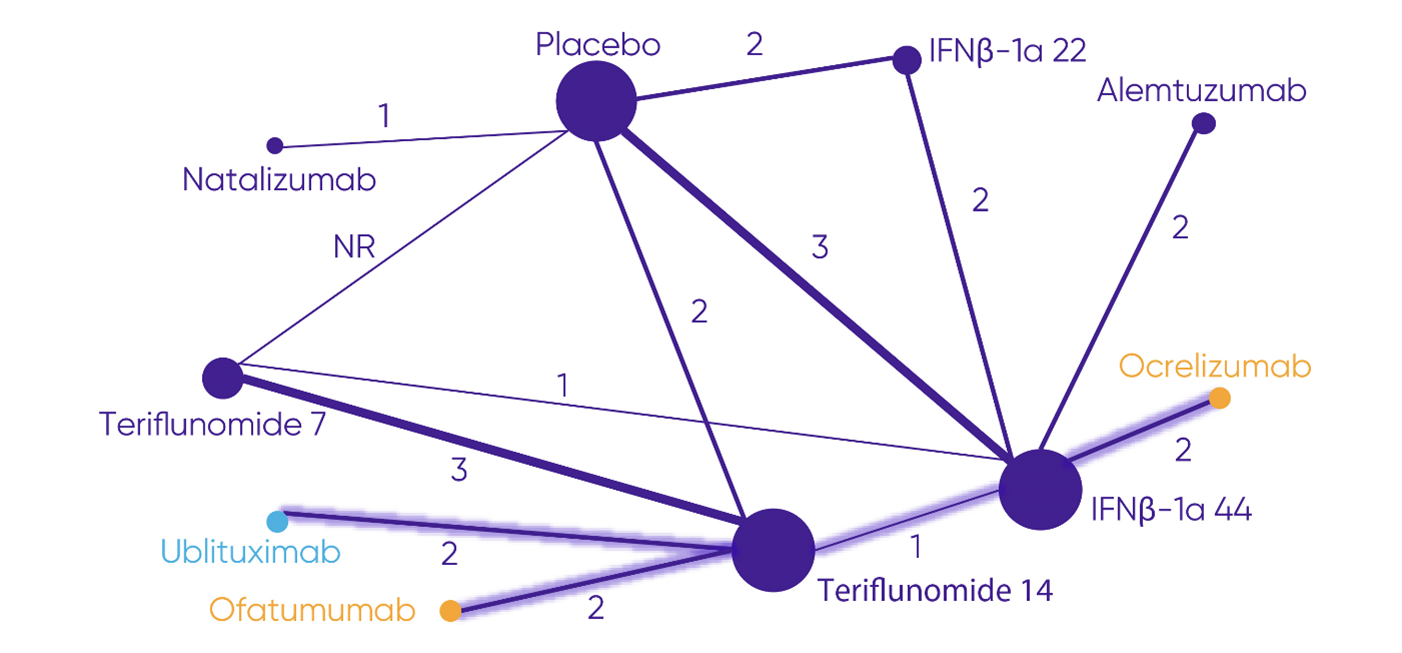

With early network mapping, manufacturers can determine if the search needs to include comparators outside the anticipated PICO.

Early network mapping uses clinical trial registries and labels of already approved treatments to identify the available trials in a given therapeutic area to construct the network that would be used for an NMA. From this exercise, we can determine:

- If the trials assessing the anticipated comparators from the HTA scope will connect in a network.

- If a connected network is not possible with only the anticipated comparators, what other treatments should be added to the SLR to create a network.

- If a connected network is still not possible with additional treatments, the other methods of ITC, such as matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC), that will be possible.

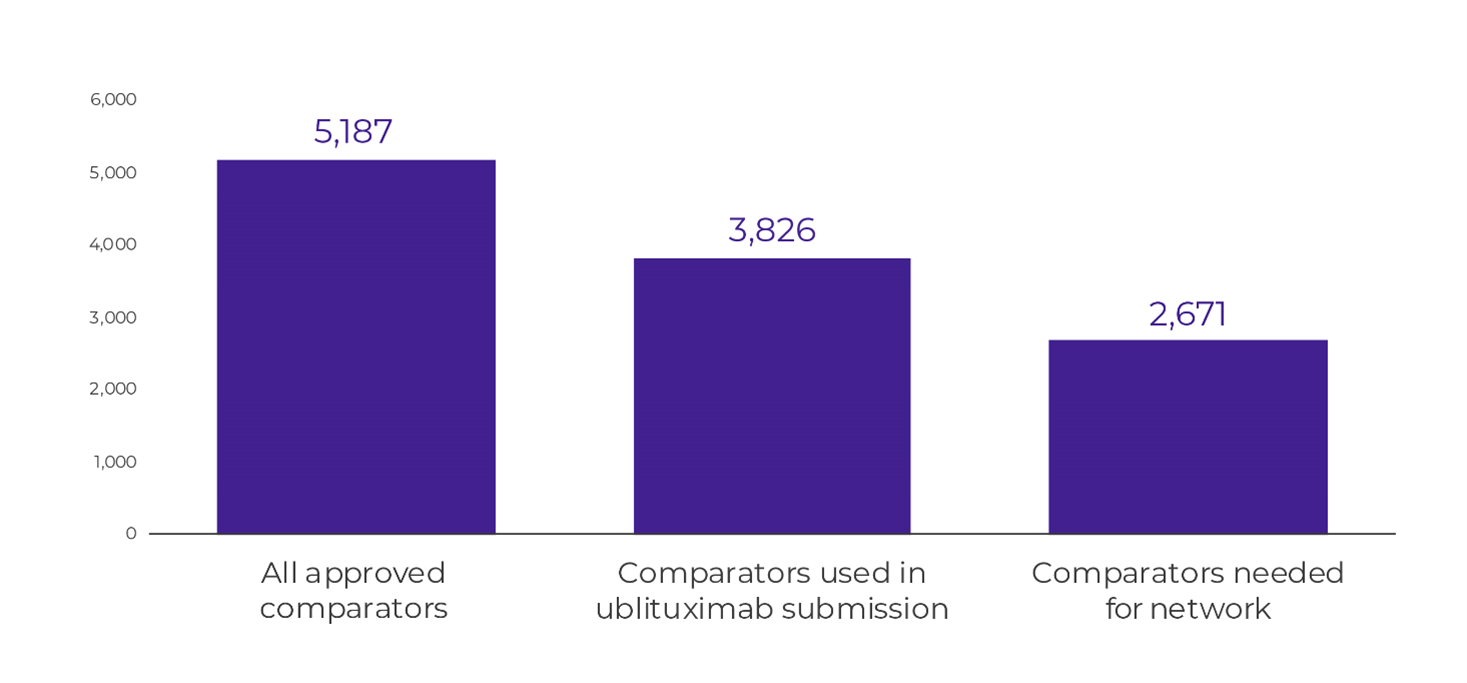

In the example discussed here, early network mapping would have shown that comparators beyond ocrelizumab and ofatumumab needed to be included in the SLR; it would also have shown that alemtuzumab and natalizumab were not needed, further reducing the number of abstracts to screen (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Number of abstracts to screen based on comparators included in search

With increasing demands for the documentation needed for HTA submissions, streamlining wherever possible can help decrease the burden placed on the manufacturer. Early network mapping adds a small amount of work upfront to decrease the effort needed for an SLR while ensuring that all the necessary evidence is identified.

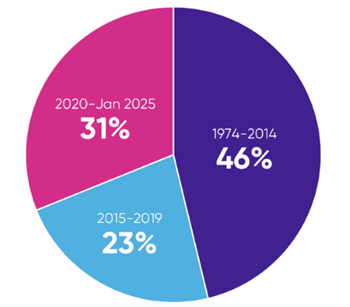

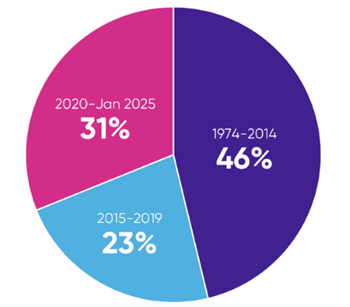

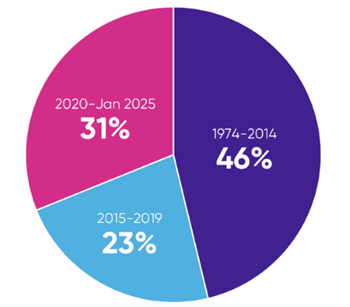

The amount of literature indexed in databases of peer-reviewed articles has been increasing exponentially. For example, over 28,000 citations for articles reporting on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) are indexed in Embase over the time period from database inception (1974) to January 2025. Of these, 54%, approximately 16,000 studies, were published in the last 10 years, and 31%, nearly 9,000 studies, were published in the last 5 years (Figure 1).

Note: An SLR conducted 10 years ago would have half the number of hits as one conducted today.

Sources

- NICE. Final scope. Ublituximab for treating relapsing multiple sclerosis. 24 June 2024a. Accessed January 13, 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta1025/documents/final-scope

- NICE. Committee Papers. Ublituximab for treating relapsing multiple sclerosis [ID6350]. 18 December 2024b. Accessed January 13, 2025. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta1025/evidence/committee-papers-pdf-13616646877

This article summarises Cencora’s understanding of the topic based on publicly available information at the time of writing (see listed sources) and the authors’ expertise in this area. Any recommendations provided in the article may not be applicable to all situations and do not constitute legal advice; readers should not rely on the article in making decisions related to the topics discussed.